Book reveals turbulent early years of The Salvation Army in Exeter

Bloodshed, beatings and broken limbs, fireworks, gunshots and riots, are not things people associate with today’s well-respected Salvation Army.

But a new book, published by The Salvation Army in its 150th anniversary year, called Blood on the Flag, highlights that in its early years these were everyday occurrences faced by members of the Church and charity.

The troubles began after the rapid early success of The Salvation Army that drew large crowds to hear preachers to town centres, and also the movement’s promotion of abstinence.

Major Nigel Bovey, author of Blood on the Flag and Editor of The War Cry, explains: “Publicans and brewers soon found that the success of The Salvation Army was causing a drop in their profits, others didn’t like the loud noises of the crowds and Salvation Army bands in the town centres.

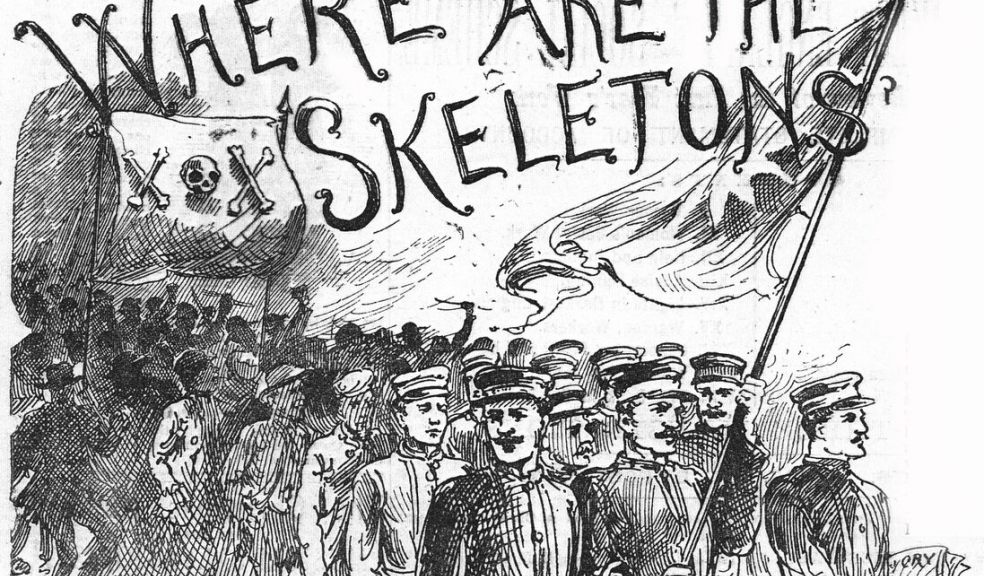

“The brewers organised opposition, nicknamed the Skeleton Army, which broke up the meetings by beating up and throwing bricks at male and female members of The Salvation Army.”

One of the Church and charity’s strategies was that if people couldn’t get to church then the church should go to them. The street meetings Salvationists held in the roughest parts of town attracted crowds, often numbered in the hundreds.

In autumn 1881, organised opposition intensifies through the formation in Exeter of the Skeleton Army. Described by the press as “roughs”, in the main, members of the Skeleton Army typically are young, male drinkers – lads who like to let their fists do the talking. But they are not all such. Exeter solicitor Edward Dent is reputedly the Lieutenant-General of the Skeleton Army.

For more than a year, the Skeletons attacked the Salvationists of Exeter on the streets and at their Church building. On more than one occasion, a mob numbered in thousands, gathered outside the hall as Salvation Army members worshipped inside. Stones are thrown and windows smashed. Skeletons try to storm the Church hall.

When Salvationists continue their street evangelism in the city’s poorest areas, the Skeletons attack. In one incident, they nearly manage to throw a Salvationist off Exe Bridge into the river. The mayor bans The Salvation Army from assembling on the streets.

When, in March 1882, Captain John Trenhail recommences marches, he and his fellow Salvationists face a mob of 2,000 people. A police officer tells him to stop singing. Trenhail refuses to do so and is arrested. Six policemen take him into custody, accompanied by a 3,000-strong crowd. Trenhail wins his day in court but the ban remains.

Attacks on Salvation Army members spread across the country including, Weston-super-Mare, Honiton and Oxford.

Some of the worst attacks occurred in 1884 in the south-coast resorts of Eastbourne, Hastings and Worthing, where members of existing Bonfire Societies were prominent in forming Skeleton Armies to rid their towns of The Salvation Army.

On Sunday 17 August, Skeletons attacked Worthing Salvationists as they marched to their hall. A fight between the police and Skeletons followed and a number of Skeletons were arrested. On Wednesday 20 August, the Skeleton Army clashed with police in protest at a number of their members being fined. That evening, 400 Skeletons paraded the streets, smashing the windows of the Town Hall and police station. The magistrates called in the troops to restore order. The Royal Irish Dragoon Guards lined up in front of the Town Hall. After a 90-minute stand-off, at 11.30pm, for the only time in Worthing’s history, the Riot Act was read and the mob dispersed.

From 1881 to 1893, the Skeleton War saw fighting in 67 towns and villages, mainly south of the Midlands. During this period, barely a week went by without a press report of an attack on The Salvation Army.

Despite brutal opposition, during this period The Salvation Army opened 1,200 new centres in the UK. It also expanded globally to 23 countries, some of which – France, Canada and Sweden – had home-grown versions of the Skeleton Army to confront.

Local communities gradually came to support The Salvation Army when they realised the assistance they offered to people in need. Today, despite those hostilities, The Salvation Army lives on, with a presence in 126 countries around the world, caring for people who are vulnerable or in need in every community.

Blood on The Flag, by Major Nigel Bovey is published by Shield, and available for sale.