Victorians enjoyed rudimentary version of Netflix, new research shows

Victorian families were able to enjoy their own version of Netflix by utilising an early form of ‘pay-per-view’ entertainment to while away winter evenings, new research has found.

Nineteenth-century households were able to have access to hundreds of images of far and exotic lands, comic scenes and classic novels, all from the comfort of their homes after magic lanterns and stereoscopes became available to hire.

While magic lanterns existed from the early 1600s, they were an expensive item which only the most affluent could hope to own.

However, the new research, carried out by Professor John Plunkett from the University of Exeter, has discovered the then state-of-the-art equipment, and thousands of lantern slides, were available for more normal families to use after opticians, photographers and stationers ‘ made magic lanterns available for loan. They also loaned out 3D photographic views after another new device, the stereoscope, became popular in the 1850s.

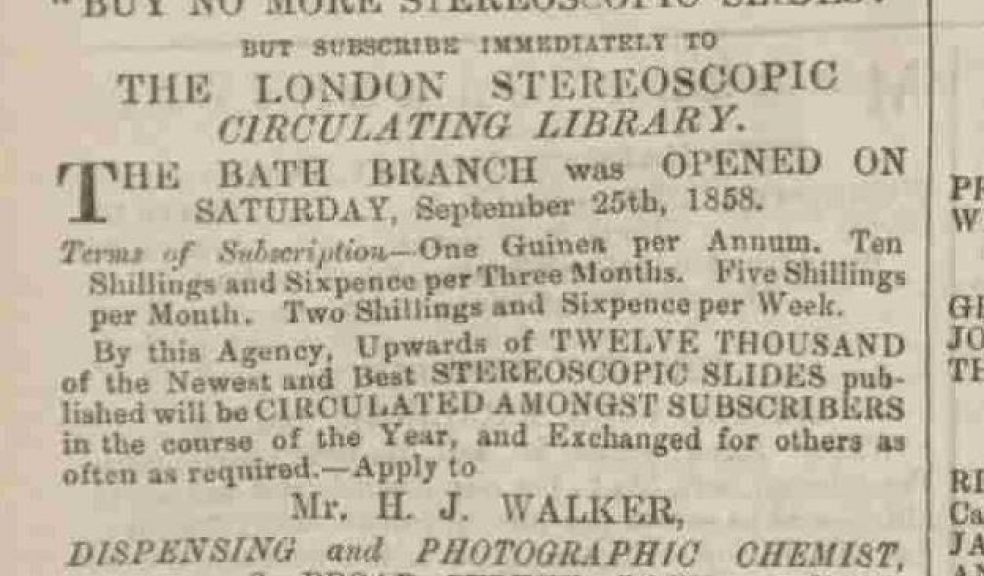

The practice, which was discovered by analysing local newspaper adverts from the period, showed that the service - which could even include hiring a lantern operator to host the viewing - was particularly popular at Christmas and for children’s birthdays.

The findings were unveiled at the British Association for Victorian Studies 2018 Annual Conference at the University of Exeter.

Professor Plunkett, from the University of Exeter’s English department, said: “We know Victorian families were enthralled by magic lanterns and stereoscopes, and now we know this drove a thriving commercial practice of hiring lanterns and slides. This really was the Netflix of its time.

“From the 1840s onwards, opticians, stationers and photographers supplemented their business by hiring viewing devices and content out, tMany of the magic lanterns were also made and operated by the opticians. Just like Netflix or the many stores that hired out videos and PC games, this was a way of getting access to much more visual media than you could ever afford to buy. ”

The earliest example found by Professor Plunkett is an advertisement in the Morning Post from 1824, when an optician on London’s Oxford Street offered ‘The Magic Lantern sent out for an evening’.

Lanterns first became available to hire in Exeter, Bristol and Plymouth from the 1840s. In Christmas 1843 Thomas Bale, a watchmaker and optician based at 11, Broadmead in Bristol advertised lanterns for hire with ‘Astronomical, Scriptural, Natural History and Comic Slides”. From the 1850s, there was a thriving culture of home entertainment. Rather than going to the pictures, the pictures would come to you.

In Christmas 1843 Thomas Bale, a watchmaker and optician based at 11, Broadmead in Bristol advertised lanterns for hire with ‘Astronomical, Scriptural, Natural History and Comic Slides”.

In November 1846 Thomas King of 2, Clare Street, Bristol, an optical and philosophical instrument maker, advertised that “he had just completed a very superior Apparatus, fitted with Achromatic Lenses, for the purposes of Privately Exhibiting the DISSOLVING VIEWS and the CHROMATROPE”.

Lanternists publicised their availability for evening entertainments during Christmas. For the Plymouth Christmas season of 1864, one Robarto, a ‘Buffo Vocalist and Exhibitor of Dissolving Views’ offered his services for his “Views from China, Japan, New Zealand, Comic Scenes, Chromotropes, & c”. Robarto was Belville James Settle, a local singer and comedian’ who was proprietor of the Exmouth Music Saloon in Stonehouse.

The magic lanterns and steroscopes available for hire were often top-of-the range versions that were too expensive for most of the public to buy: hiring was also a way of seeing the latest slides or 3D views – whatever the latest media sensation was. In December 1859, Lancaster’s Fancy Repository in Bristol advertised a new revolving stereoscope for hire that allowed users to view 208 scenes in sequence. In November 1859, R.W. Bingham advertised a machine for hire that that two people could view at once and which held 108 stereographs. Local firms such as Bingham had libraries of 3,000 3D scenes that people could subscribe to, while others had libraries of several thousand lantern slides.

Professor Plunkett said: “Hiring a lantern and slides was very much an expensive treat for the middle classes, especially if they wanted a lanternist too. As the century went on it became much more affordable. After 1880, local businesses were pushed out of the market as the lantern slide industry became more centralised.”

A labourer might earn 15s a week while a typical subscription to a slide library could be around 5s for one month and £1 1s for twelve months. The London Stereoscopic Company provided access to 12,000 cards for 2s6d per week.

In 1877, O’Handlen and Co., a Bristol optician, offered a package consisting of 100 slides, projections that were 8-12ft in diameter, a screen, and an attendant and a descriptive reading, all for 10s6d.

Dissolving views were extra, and cost 15s for an evening. In the mid-1860s, the Grant Brothers, who ran stationer’s outlets in Exeter and Torquay, offered magic lanterns for hire from 7s 6d per evening; By 1892, the loan of lantern and 3 dozen views from Charles Limpenny in Plymouth was only 5s 6d.

Although, by the middle of the 20th century the magic lantern had gradually evolved into the common ‘slide projectors’ seen in many homes and institutions, Victorian retailers pioneered a model of media consumption that we now take for granted.